Drash for Congregation Ner Shalom‘s Shabbat service, February 18, 2022, a special service for Jewish Disability month.

When the Hebrews left Egypt and slavery behind, nobody said, you can come only if you can walk for endless miles. Or see the path. Everyone who wished to go, went.

When they came to the Red Sea, every last traveller got across safely. Including those who couldn’t understand the directions.

At Mount Sinai, each and every person there experienced the Revelation. Even being born wasn’t a prerequisite.

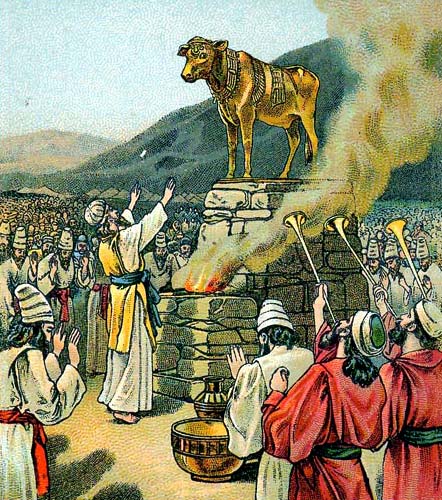

So here we are in Parashat Ki Tisa. Moses has been on the top of the fire-covered mountain for over a month and some of the Hebrews think he’s never coming back. They compel Aaron not to replace God, but to replace Moses.

When the people saw that Moses was so long in coming down from the mountain, the people gathered against Aaron and said to him, “Come, make us a god who shall go before us, for that man Moses, who brought us from the land of Egypt—we do not know what has happened to him.”

Exodus 32:1

Most translations say “make us a God.” The words in Hebrew are עֲשֵׂה־לָ֣נוּ אֱלֹהִ֗ים (ahsay lanu elohim), literally, “make for us Gods.” (God often being in the plural in Torah.) But some commentators interpret it as “make us a judge.” A judge to take Moses’ place. A new intermediary between the people and God.

Why did they need an intermediary at all? In part, because God was terrifying. Direct communication physically hurt. Also because of new laws where the consequences for getting them wrong could be fatal. The Hebrews started learning these laws at Marah, the first stop after the Red Sea, but the Revelation brought hundreds more.

At first Moses was the one to guide people through the laws, but then he set up a court system. Extended family units handled the simple questions and disputes. Then judges at various levels took more difficult ones. Anything that required God to weigh in went through Moses. Except now he was unreachable. Or maybe dead.

Moses left his brother Aaron and nephew Hur in charge of the courts, but it wasn’t the same. As the weeks went on, the people wondered if, without Moses, God would leave them. Or destroy them. Out of desperation, they rioted until Aaron agreed to help.

They asked Aaron for a human intermediary but Aaron instead made a statue. An untalking, unfeeling, unhelpful hunk of gold shaped like a calf. From gold jewelry he told the people to take from their own ears. Aaron hoped to stall them long enough for Moses to return and he almost succeeded. But I keep wondering, why a calf? Why a statue at all?

The popular fiction is that Aaron made an idol, a false God for the people to worship. But Jewish commentators don’t believe that. Some people did go on to worship the calf, but that was not the intent of the Hebrews or of Aaron.

According to the 18th century Moroccan Rabbi known as Or HaChaim:

[The people] wished to construct some symbol of a celestial force which would remind them of G’d in Heaven. The people who initiated the golden calf did not deny for a single moment either the primacy of G’d or the fact that He had made heaven and earth. They merely wanted a go-between them and G’d [similar to when all the people had asked Moses to be their go-between during the revelation at Mount Sinai. Ed.]

Or HaChaim on Exodus 32:1:3

Egypt had many cow gods, including Hathor and Apis, and a tradition of gods using bulls as mounts. I can imagine the Hebrews thought of the golden calf as an invitation. Yah, we’ve got your cozy seat right here. Come and hang with us.

This isn’t so absurd. At the very moment that Aaron was forging the calf, God was up on the mountain with Moses giving him instructions for the mishkan, including how to make two gold cherubim on the cover of the Ark.

God tells Moses:

There I will meet with you, and I will impart to you—from above the cover, from between the two cherubim that are on top of the Ark of the Pact—all that I will command you concerning the Israelite people.

Exodus 25:22

What’s the difference between God sitting on a calf and God appearing between two angels? The angels were hidden inside a tent, where only Moses and a few select others could go. The calf was out in the open, for anyone to see. In a place where anyone could come to listen to God.

The tale of the Golden Calf isn’t about disability. But it is about accessibility. About gatekeepers and privilege. Judaism isn’t a religion that requires intermediaries; we’re each encouraged to have our own personal relationship with God. As too are the Israelites. The intermediary—the go-between—that they need is to subdue the firehose of conversation with God.

I can’t help but think of disability issues though, about how so many of us have had intermediaries forced upon us. Helpers we don’t want or need. Or that we need less often than others think. Sometimes we do need someone to speak for us or to listen and remember. Or an interpreter, a buffer, assistance with a task. If we rely on someone and suddenly they’re not there, what do we do?

It didn’t go so well with the Golden Calf. The Hebrews’ violence and hedonism aren’t excusable. But their actions began as fear, as an attempt to find what was missing. They needed Moses to interpret between them and God. But they didn’t need for God to be hidden away where only priests had access. They may not have known that that was the plan when they confronted Aaron, but what they asked for, what they built, was something open to all, just like the rest of the Exodus had been so far. For everyone.

(With thanks to Dr. Jeffrey Tigay and his article The Golden Calf at My Jewish Learning.)

0 responses so far ↓

There are no comments yet...Kick things off by filling out the form below.

Leave a Comment